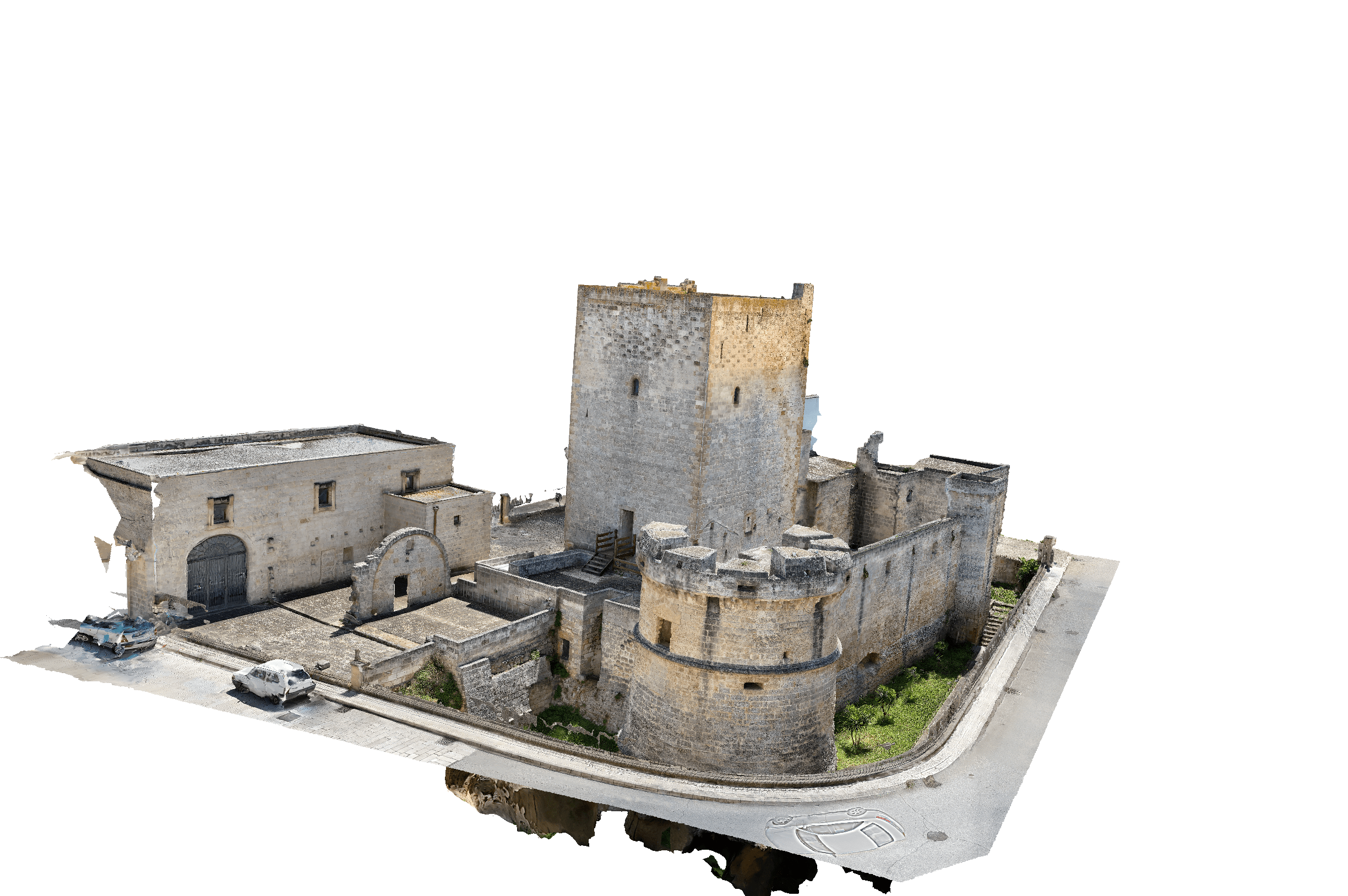

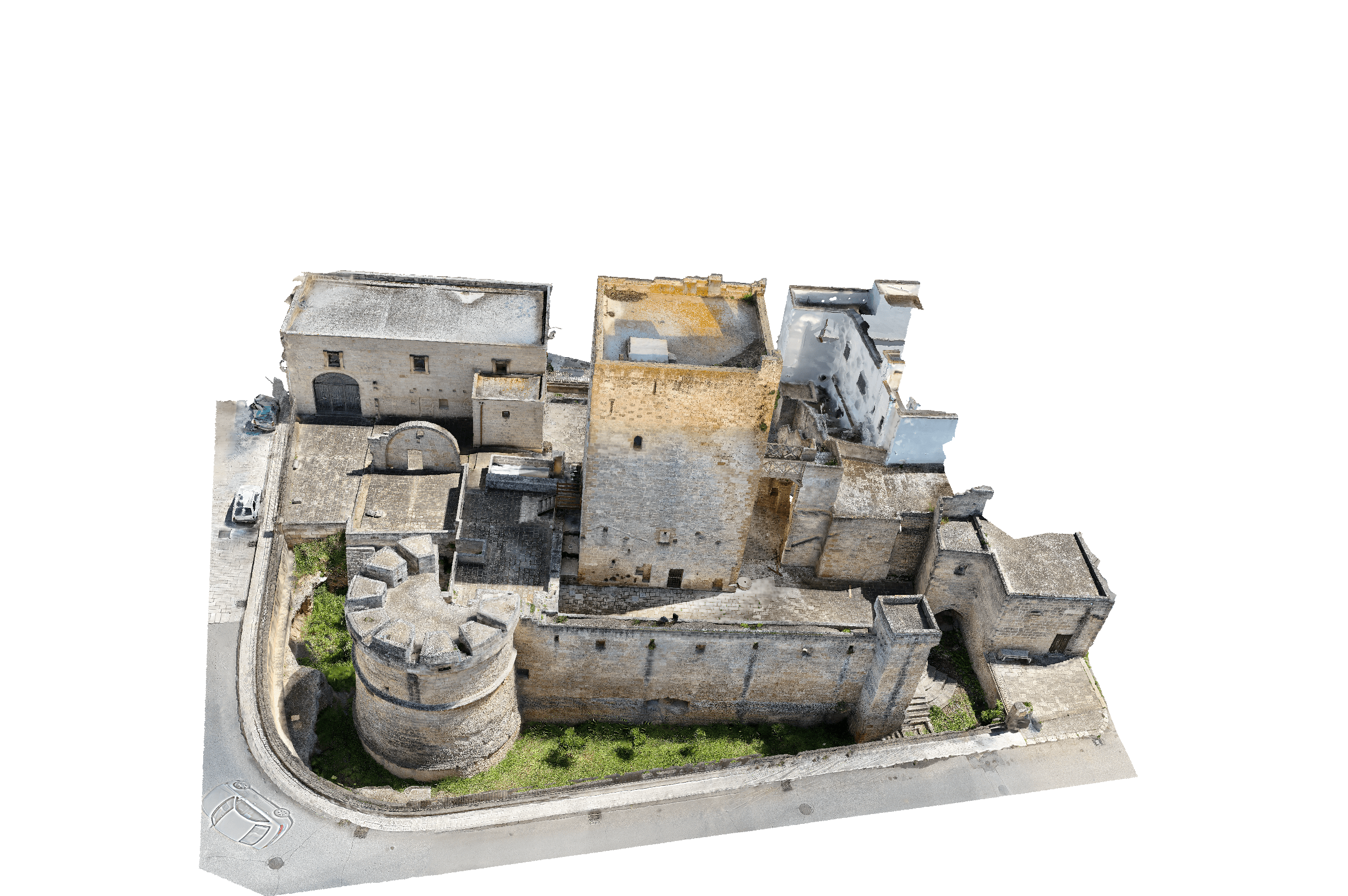

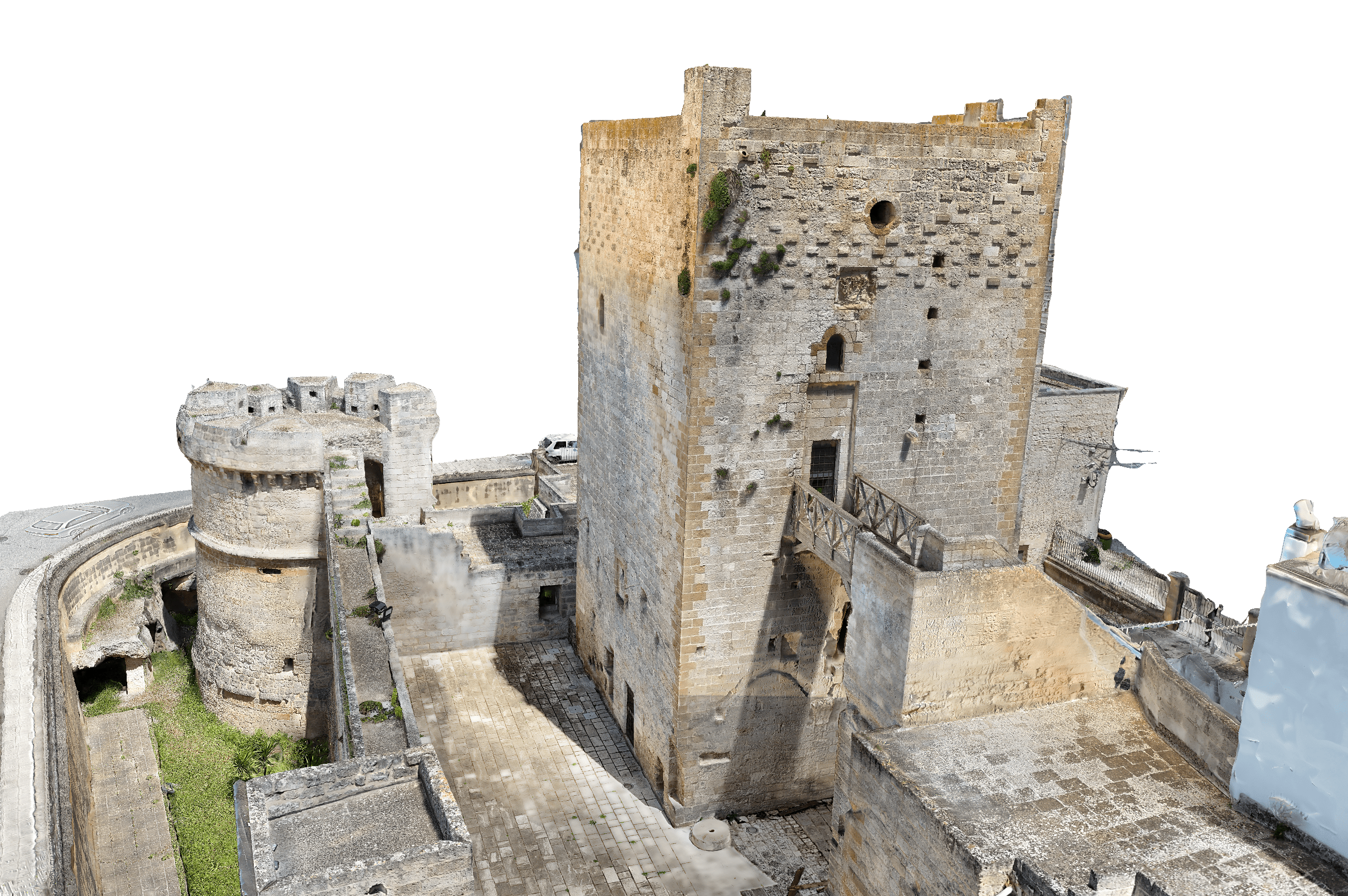

Nel ventre della pietra , Il Torrione di Avetrana e il suo Trappeto. Ogni paese ha un cuore. Ad Avetrana, questo cuore è fatto di pietra, silenzio e memoria. Se chiudi gli occhi e ascolti il vento che scivola tra i vicoli, potresti sentire ancora l’eco dei colpi di piccone, lo scricchiolio di una carrucola, lo scalpiccio lento di un mulo sotto terra. Sì, sotto terra. Perché ad Avetrana la storia non si legge solo nei libri. Si cammina. Si tocca. Si respira. E comincia da qui: da una torre che ha visto tutto. Benvenuti al Torrione. Costruito prima del 1378, secondo fonti d’archivio, ma probabilmente più antico, databile tra XI e XII secolo, il Torrione nacque in un tempo di paura. I casali di Santa Maria, Modunato e San Giorgio erano stati devastati dalle incursioni saracene. Gli oritani – abitanti di Oria – si rifugiarono qui e costruirono una torre in càrparo, una pietra dura locale, resistente e dorata al sole. Attorno a lei, lentamente, nacque Avetrana. Il nome, secondo alcuni studiosi, deriva da Veterana: la terra donata ai veterani normanni per ricompensa. Il Torrione era il cuore difensivo del borgo, circondato da fossato, ponte levatoio, bastioni, torri minori. Sulla facciata sud, scolpita nella pietra, ancora oggi si può osservare una figura enigmatica: un toro con volto umano. Simbolo di forza? Firma dei costruttori? Emblema di Oria? Nessuno lo sa con certezza. Ma resiste, come tutto il resto. Con il tempo, però, la guerra si fece lavoro. Sul fianco della torre fu scavato un frantoio ipogeo: il Trappeto della Cantina. Scendere oggi in quel trappeto significa entrare in un mondo antico: il tufo trattiene il calore, l’aria è ferma e il profumo è denso. La temperatura resta costante: tra i 18 e i 20 gradi. Perfetta per la trasformazione delle olive in olio. Dentro il trappeto, tutto aveva una funzione. C’erano due tipi di torchio, a testimoniare l’evoluzione della tecnica nel tempo. Il più antico era il torchio alla calabrese: con due viti verticali, incastonate nel pavimento in pietra e nel soffitto, dove il travone scendeva lentamente per spremere i fiscoli pieni di pasta d’oliva. Solido ma lento, era diffuso nel Regno di Napoli fino all’inizio dell’Ottocento. Poi arrivò il torchio alla genovese, con una sola vite centrale, introdotto nel Salento dal XVIII secolo. Era più compatto nella struttura, ma funzionava con lunghe aste infilate nei fori laterali alla base della vite, richiedendo comunque spazio intorno per essere manovrato. Il vitone era fissato in alto a un blocco in legno o pietra, e poggiava su una base in pietra dura. Garantiva una spremitura più profonda e più rapida. Con il tempo, sostituì il torchio calabrese, specialmente nei frantoi più grandi o modernizzati. In quelle viti, in quei meccanismi, c’è tutta la storia di una comunità che imparava, adattava, migliorava. Una storia fatta di fatica, ma anche di ingegno. Il lavoro iniziava in autunno e finiva in primavera. Giorno e notte. Senza sosta. L’unico giorno di riposo: l’8 dicembre, festa dell’Immacolata. A capo di tutto, c’era il nachiro. Forse da naqīb – guida, capo – o forse da “nocchiero”, il timoniere. E lo era davvero: il timoniere del frantoio. Supervisionava tutto: turni, tempi, resa dell’olio, offerte dei clienti. Sapeva riconoscere la qualità della pasta d’oliva, decidere quando spremere, quando aspettare. Era una figura Spesso forestiera però autorevole, esperta e temuta. I frantoiani vivevano nel trappeto per mesi. Dormivano su stuoie, vicino agli animali. Si scaldavano al focone. Mangiavano poco, lavoravano molto. E cantavano ,Per non crollare ,Per stare svegli. Per sentirsi ancora vivi. Sopra, la torre restava attiva. Al piano terra: una stalla per gli animali da lavoro. Al piano superiore: un magazzino per paglia, foraggi e attrezzi agricoli. All’ultimo piano: una camera da affitto per braccianti o viaggiatori di passaggio. Tutto era pensato per essere utile, essenziale, connesso al ciclo del lavoro rurale. Intorno, tre mulini macinavano grano e biade per conto del popolo. C’era poi l’olio lampante: più scuro, più denso, meno nobile. Ma essenziale. Serviva a illuminare case, chiese, conventi, arsenali, porti, navi. Veniva caricato su carri, portato a Taranto, poi a Napoli, e da lì esportato in tutto il Mediterraneo: Marsiglia, Alessandria, Tunisi, Odessa, perfino Russia. Era il fuoco liquido del Sud. La luce dei poveri. Il Torrione fu anche spettacolo. Tra gli anni ’30 e ’50, ai suoi piedi si rideva. Si allestivano spettacoli di marionette. Si proiettavano film su lenzuola bianche, sotto le stelle. I bambini sedevano su cassette di legno, le famiglie portavano le sedie da casa. Era un teatro popolare, un cinema di pietra. Poi arrivò la televisione. Era il 1954 quando la RAI iniziò le sue trasmissioni. E ad Avetrana, qualche anno dopo, quel marchingegno straordinario fece capolino per davvero. Era il 5 novembre 1957, quando la troupe di Telesquadra – programma itinerante della Rai – allestì una sala regia proprio nei locali del vecchio telecamere, microfoni, artisti e interviste portarono lo spettacolo tra le pietre del paese. La gente si radunava attorno ai pochi televisori disponibili, spesso ospiti dei più fortunati. Era festa. Era stupore. Poi, piano piano, la magia si spense. E il silenzio tornò. Oggi il Torrione è silenzioso. Ma non muto. La pietra conserva tutto. Ogni graffio. Ogni scalino consumato. Ogni buco nel muro. Se passi da Avetrana, non guardarlo solo da fuori. Fermati. Toccalo. Ascolta. Perché questa torre non è solo un monumento. È una voce antica, che ha ancora molto da dire

In the Belly of the Stone The Torrione of Avetrana and its Trappeto Every town has a heart. In Avetrana, this heart is made of stone, silence, and memory. If you close your eyes and listen to the wind slipping through the alleys, you might still hear the echo of pickaxe strikes, the creak of a pulley, the slow clatter of a mule underground. Yes, underground. Because in Avetrana, history isn’t just read in books. It’s walked. It’s touched. It’s breathed. And it begins here: with a tower that has seen everything. Welcome to the Torrione. Built before 1378, according to archival sources, but likely older—dating back to between the 11th and 12th centuries— the Torrione was born in a time of fear. The hamlets of Santa Maria, Modunato, and San Giorgio had been ravaged by Saracen raids. The Oritani—inhabitants of Oria—took refuge here and built a tower in carparo, a hard local stone, resilient and golden in the sun. Around it, Avetrana slowly came to life. The name, according to some scholars, derives from Veterana: land granted to Norman veterans as a reward. The Torrione was the defensive heart of the village, surrounded by a moat, drawbridge, bastions, and smaller towers. On its southern façade, carved in stone, you can still see an enigmatic figure: a bull with a human face. A symbol of strength? A builder’s signature? An emblem of Oria? No one knows for sure. But it endures, like everything else. Over time, however, war gave way to labor. Carved into the side of the tower was an underground olive press: the Trappeto della Cantina. To descend into the trappeto today is to enter an ancient world: the tuff walls retain warmth, the air is still, the scent intense. The temperature remains constant: between 18 and 20 degrees Celsius. Perfect for turning olives into oil. Inside the trappeto, everything had a purpose. There were two types of presses, testifying to the evolution of technique over time. The oldest was the “Calabrian” press: with two vertical screws set into the stone floor and ceiling, where the large beam slowly descended to press the disks full of olive paste. Solid but slow, it was common in the Kingdom of Naples until the early 1800s. Then came the “Genoese” press, with a single central screw, introduced into Salento in the 18th century. More compact in structure, it worked with long rods inserted into side holes at the screw’s base, still requiring space around it to be operated. The screw was fixed at the top to a wooden or stone block, and rested on a hard stone base. It allowed for deeper and faster pressing. Eventually, it replaced the Calabrian press, especially in larger or modernized mills. In those screws, in those mechanisms, lies the story of a community that learned, adapted, improved. A story made of hardship, but also ingenuity. Work began in autumn and ended in spring. Day and night. Without pause. The only day of rest: December 8th, Feast of the Immaculate. At the helm of it all was the nachiro. Perhaps from naqīb—meaning guide or leader—or perhaps from “helmsman”. And that he was: the helmsman of the oil mill. He oversaw everything: shifts, timing, oil yield, customer offerings. He knew how to judge the quality of olive paste, when to press, when to wait. Often a stranger, but respected, experienced, and feared. The oil workers lived in the trappeto for months. They slept on mats, near the animals. They warmed themselves at the fire pit. They ate little, worked hard. And they sang. To keep from collapsing. To stay awake. To feel alive. Above, the tower remained active. On the ground floor: a stable for working animals. On the upper floor: storage for straw, forage, and farm tools. On the top floor: a rental room for laborers or passing travelers. Everything was designed to be useful, essential, connected to the rhythm of rural work. Nearby, three mills ground wheat and grain for the people. And then there was the lampante oil: darker, denser, less refined. But essential. It lit homes, churches, convents, arsenals, ports, ships. It was loaded onto carts, taken to Taranto, then to Naples, and from there exported throughout the Mediterranean: Marseille, Alexandria, Tunis, Odessa—even Russia. It was the South’s liquid fire. The light of the poor. The Torrione was also a place of entertainment. From the 1930s to the 1950s, laughter echoed at its feet. Puppet shows were staged. Films were projected on white sheets under the stars. Children sat on wooden crates, families brought chairs from home. It was a people’s theater, a stone cinema. Then came television. It was 1954 when RAI began broadcasting. And in Avetrana, a few years later, that extraordinary contraption finally arrived. It was November 5, 1957, when the Telesquadra crew— an itinerant RAI program— set up a control room right in the old tower’s rooms. Cameras, microphones, artists, and interviews brought the show among the village’s stones. People gathered around the few available TVs, often as guests of the lucky few. It was a celebration. It was wonder. Then, slowly, the magic faded. And silence returned. Today the Torrione is silent. But not mute. The stone holds everything. Every scratch. Every worn step. Every hole in the wall. If you pass through Avetrana, don’t just look at it from the outside. Stop. Touch it. Listen. Because this tower is not just a monument. It is an ancient voice that still has much to say.